HOW A RADICAL IDEA IN 2002 CHANGED WRESTLING HISTORY

By: Thom Fain, with research & assistance by Sam Gladen

The process of New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s U.S. acculturation has been building, like a crescendo, for nearly twenty years. Antonio Inoki himself first tried to establish a U.S. territory for NJPW, building out his business from a small warehouse in Santa Monica in April 2002. From Inoki’s vantage point, the King of Sports had a strong incentive to compete in California’s wrestling market – a bold endeavor that has since culminated in the incarnation of New Japan of America.

Inoki’s concept of a U.S. base of operations began to emerge after New Japan’s successful, but at times contentious, relationship with WCW.

“What people don’t realize is how important the Inoki Dojo was,” veteran manager and former WCW talent Sonny Onoo told us in an interview. Onoo described how New Japan’s key players wanted a training hotspot, which would invite a cadre of future superstars into its doors as an alternative to WWE developmental territories.

“Americans think in terms of ‘what’s it cost, can we all make money,’ which is pretty superficial. Most Japanese businesspeople won’t do business unless there’s a relationship. It’s not about short-term what’s good for us, but looking at things long-term. Japan won’t do business unless it’s a good relationship. That’s what Mr. Inoki and Eric Bischoff, Brad Rheingans, Masa Saito – that’s what we had going on. Masa Saito had the blessings to establish Inoki Dojo.”

Brad Rheingans – a former U.S. olympic coach – didn’t care so much about business. He cared about wrestling. Rheingans (credited for training the likes of Scott Norton, John B. Layfield aka JBL, and others) had a knack for smartening the talent up to New Japan’s strong-style brand of puroresu, even as sports entertainment came to define the era. Masa Saito, according to historian & commentator Chris Charlton, helped build a bridge between the McMahons and Inoki during NJPW’s brief partnership with WWF. Saito – a legit badass in and out of the ring, perhaps most famous for creating the “prison lock” while in prison and wrestling Inoki on a deserted island – scouted and trained the likes of Vader, Kento Miyahara, and Masa Kitamiya.

➡️ NJPW Strong Energy 2004 – Toukon Festival Part II, 04/24/2004

pic.twitter.com/seZZiorRm8— Nicholas ~ ニコラス⚡️ (@nikdluffy) September 20, 2022

Saito and Rheingans were also good friends from their days in Minnesota and the AWA, even wrestling as a tagteam in Russia while training USSR talent during Inoki’s obsession with a post-Soviet NJPW expansion effort. Inoki knew he could count on the pair to recreate the structure in America, and find Western wrestlers capable of recreating the magic of that 1989 Tokyo Dome IWGP Championship tournament.

“Inoki officially retired in ‘98 and moved to LA right away… he is the only person I know who got a U.S. green card in two weeks,” said MP editorial advisor Fumi Saito, who has covered the sport for 40 years. “And that’s when the Inoki Dojo idea came up. His daughter and her husband were running the business side of things by then.” It was somewhat of a challenge for the Americans involved to understand the value proposition for New Japan’s Inoki Dojo, but the team of trainers, wrestlers, producers and bookers could lean on Simon Inoki (his son) as an ally in business.

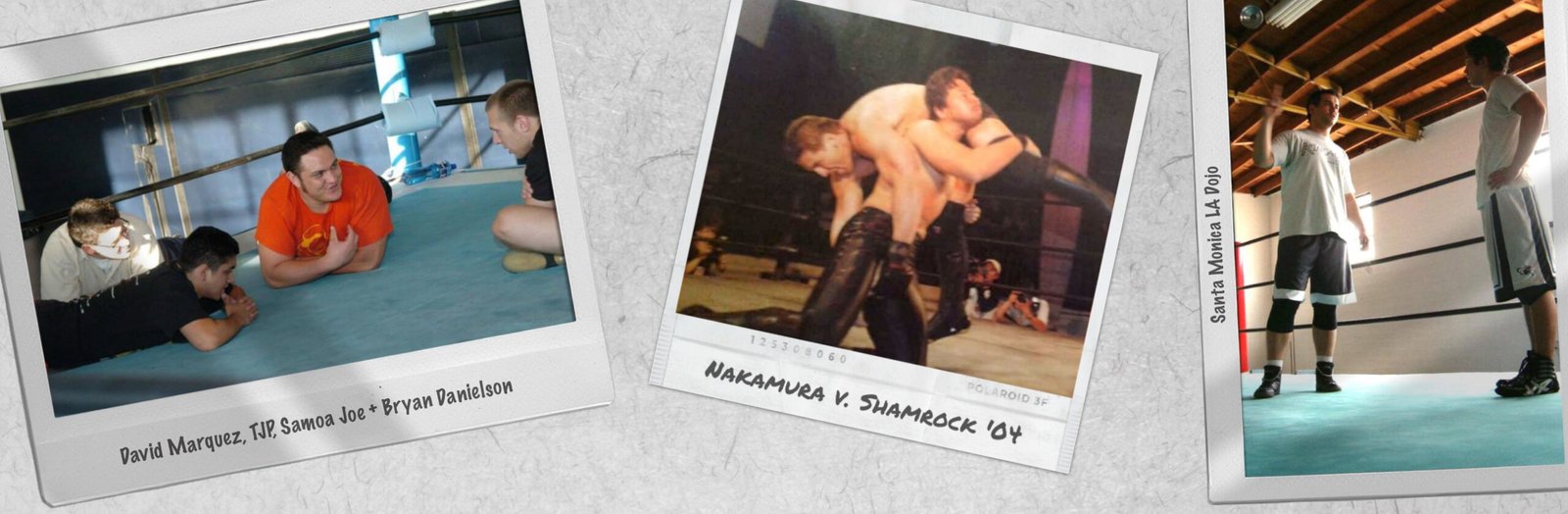

“Mr. Inoki was always such a mystery – and I’m not talking his in-ring character,” said David Marquez, a TV producer and wrestling promoter heavily involved with New Japan’s U.S. efforts.

“I feel he enjoyed training the young talent very much, but [he didn’t share] a clear vision for the LA Dojo… although, I do feel Simon had a roadmap and we did our best to follow it.”

The opening of Inoki Dojo was attended by some of the best and brightest of the early aughts: Kensuke Sasaki, Masahiro Chono, and Yuji Nagata. The event was also attended by MMA standouts Don Frye (another Rheingans trainee), Bas Rutten, Wallid Ismail, Justin McCully (aka Justin Sane), and former WWE superstar Joanie “Chyna” Laurer.

Inoki Dojo would serve as a roadhouse for Southern California-based MMA fighters, bringing Eastern training methods to the bustling California scene, with pioneering workouts centered around Muay Thai, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, and Yoga.

Rocky Romero, a key player in helping NJPW grow in popularity in the West, explained to Monthly Puroresu how the original dojo grew to respect Inoki’s ambitions.

“I think Inoki was looking to shock the system like he had done before with UWF and wanted the LA Dojo to represent his feelings about the industry,” Romero said. “Back then, there were a lot of politics and struggles between New Japan purists and Inoki, and the LA Dojo young lions were caught in the middle of that.”

Jyushin “Thunder” Liger, ever the NJPW emissary, would fly over and host wrestling seminars from the Inoki Dojo. Bryan Danielson was basically living in LA while training there and a young, blonde CM Punk flew himself in for appearances, while Samoa Joe further developed his unique style of wrestling. The Inoki Dojo became a safe haven for talent, trainers, and figureheads who wanted experience outside of WWE and its community would infamously push professional wrestling beyond the sports entertainment portrayal of the sport quickly becoming homogenous on TV.

“It was an incredible opportunity,” explained Ricky Reyes, who returned to work for New Japan in 2021. “I was trained by Mr. Inoki himself along with world-class MMA fighters and coaches for years. And, I’ve met everyone in NJPW from past to present, developing a deep love for New Japan that I share with the fans.”

There were, of course, other alternatives – but none with the brand name recognition of NJPW. Ring of Honor of 2002 was, at that time, an indie run by leftover ECW staff. It was very much a Wild West of journeymen and young guys who needed the work, but had no spot in WWE’s performance center. Those wanting to experience the old school way eventually found themselves in LA.

“It wasn’t even part of Inoki’s plan, but a lot of guys started living there at the dojo,” Fumi Saito explained, “sometimes in the attic. A very interesting time period, when you look at all the personalities.”

Wrestlers in Southern California who previously had worked in UPW/ZERO-1, EPIC, and ROH found the Tokyo-styled training sessions to be a bastion for professional growth, lining up at the door for an opportunity to work for the company – and incorporate its style into their ring work. “We just wanted to show the world what NJPW was all about,” explained Reyes. “Today… it’s everything, and then some, of what we all wanted to do in 2002 to 2004.”

“I think it speaks to the value of those tools and lessons,” TJ Perkins told MP, “specifically to what we crafted in Inoki Dojo, because two decades later it’s still of high value – and perhaps the most common tools being used [to evaluate next generation talent].”

As SoCal wrestling fans clamored for an alternative to WWE, New Japan found no shortage of publicity after Inoki announced they had signed a TV deal to broadcast their U.S. based matches in 2003 – 04. Much of the action, he said, would take place at the Pacific Media Expo in Anaheim, California. The show was produced by David Marquez.

“My job title was VP of International Division, which meant I was to handle most business operations outside of Japan,” Marquez told MP. “The internet was much newer and marketing to non-Japanese was very difficult. Also, I did not know that the events were in high demand. In the way of distribution deals, we had one. I made an agreement with Los Angeles digital station KVMD-TV, and the true reason I wanted to be on this station was because they had a really nice studio not far from the dojo in Santa Monica… I knew the Dojo itself would not be good for TV production, and I wanted a professional place to shoot.”

It would be branded NJPW-USA Toukon Fighting Spirit, and feature four pre-taped matches from the Dojo events. The first tapings took place on June 26, 2004, including dojo residents and local independent talents. The show was well-received by fans both in attendance and watching on TV, not in the least because of some surprise starpower. The first episode of NJPW-USA Toukon Fighting Spirit featured a match from Japan with Chyna facing off against Chono.

“New Japan really wanted a legit ‘sports feel’ to the matches,” said AEW Ref. Rick Knox, who worked for Inoki as referee of Toukon Fighting Spirit. “If you see that footage, I’d have one wrist taped with blue, one with red; that signified the ‘red’ and ‘blue’ corners for each specific competitor. During any sort of title match, they preferred I present the championship belt at waist level as opposed to high overhead – I’d present it to each side of the ring and fans, ending up faced towards the hard camera.”

Knox recalled several unique puroresu facets creeping onto the scene from Inoki’s experiment, (such as the international 20 count) as well as delighting the suits in attendance, who looked on in hopes of gaining market share on the coast opposite of McMahon. “Oftentimes there’d be many high level Japanese executives and their families in attendance, suit and tie affairs, all very official,” Knox recalled. “It was always a thrill getting to work with top level international talent.”

After airing only five episodes of their show NJPW pulled the plug on the NJPW-USA Toukon Fighting Spirit. New Japan would not be deterred for long however announcing in a press release that the show would be going on hiatus and the promotion would be instituting “Phase II” of their plans for western expansion, by joining a rebranded National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), itself struggling to maintain relevance after multiple sales and divestitures.

“The first thing I did when I had the chance was to reclaim the NWA membership and started recruiting,” remembers Marquez. “This is how Fergal ‘Prince’ Devitt, who I recall was an NWA owner with NWA Hammerlock, got his start in New Japan – in addition to Karl Anderson, Mikey Nicholls and Hartley Jackson.”

The most notable event from this partnership was a cross-promoted American Best of Super Juniors tournament taking place April 5, 2005, in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Unlike the Japanese version of the tournament, it was a one-day event featuring Inoki Dojo members alongside Ring of Honor talents.

“I reffed the entire event and can tell you Mr. Inoki was there,” recalled Ref. Knox. “And afterwards, he said I was the best part of the whole show! [laughs] Considering guys like Samoa Joe, Danielson, Rocky, TJP were in the tournament… I took that as extremely high praise. I remember this guy coming through for a spell named Shinsuke Nakamura, and I was impressed. Just a young boy at the time doing U.S. tours. I remember him either working the ticket window, or maybe it was the snack bar selling nachos. Point being [before becoming a superstar] he did whatever the office needed!”

The show itself was not destined for success, however, as televised wrestling was dominated by WWE programming. That’s not to say New Japan’s early efforts weren’t marketable. Industry insiders, wrestlers, and the hardcore fans who would later make Pro Wrestling Guerilla (PWG) and ROH famous, ensured its legacy would live on. The tape traders and DVD collectors would hunt for the type of strong-style that Inoki wanted wrestlers in the West to learn and adopt. “We had great cards, but I don’t think the public understood ‘Inoki-ism’ or Toukon,” Marquez demurred. “As the producer and director, the hardest part of that job was turning a warehouse into a TV studio. We had nothing but the ring there, so sorting out the lights, TV production truck and most importantly air conditioning!”

The final match of NJPW-USA Toukon Fighting Spirit saw Rocky Romero (as Black Tiger IV) face off against Dragon Soldier B (Kendo KaShin) in a losing effort. The event was panned by fans and critics alike, and not long after Antonio Inoki would sell his shares in NJPW to video game publisher Yuke’s. The last Inoki Dojo event in Santa Monica took place on August 25, 2006 where Romero defended his CMLL Super Light Heavyweight Championship against Mikey Nicholls.

“I knew the majority of the people at the Inoki Dojo had star quality and I wanted to add to that,” Marquez told MP.

“The local wrestling scene was smaller then, but there was a lot of initial hype for the shows,” explained SoCal Uncensored’s Steve Bryant. “It quickly went away because the shows were 90% locals that we could already see [perform] every week, with very few wrestlers coming over from NJPW. The matches were usually really short. Like, they had a match between Shinsuke Nakamura, and Ken Shamrock that went to a five minute draw!”

Still, the seeds had been planted for strong-style puroresu to grow in new soil with a unique wrestling philosophy separate from WWE, just as the McMahons began to supersize their capitalization on sports entertainment.

2002 #LAdojo #njpwworld #njpw50th #NJPW Originals… pic.twitter.com/pOJ1o5FPUR

— Ricky Reyes (@RickyReyes01) September 23, 2022

“We had a fearlessness in the original LA Dojo training, and our performances,” TJP said. “A lot was being asked of us that was out of the ordinary. We had to learn to fight, we were asked to perform multiple styles by multiple bosses. We were in the middle of an office ideology and culture shift.”

That shift in NJPW’s philosophy happened concurrently with the explosion of the internet, a shift in fan perception of the sport and of kayfabe, and a downturn in Japan’s wrestling business as a whole. The experiment led to the end of Inoki’s relationship with the office in Tokyo, and was part of the reason NJPW expenses led to its sale to Yuke’s. New Japan wanted to cut ties with Inoki, and they struggled until the emergence of the dark ages. They would not last as young lions Kazuchika Okada and Tetsuya Naito awaited assignments from head booker Gedo – who was preparing a complete makeover of New Japan’s in-ring marketability.

Just like the Three Musketeers held the glue of New Japan together during its turbulent times, the late-00s generation of talent provided hope for the company. Inoki’s dreams from those Malibu hills didn’t die – just faded for a while, as the domestic product regained its cultural relevance.

So, too, would Japanese talent be waiting to perform in front of American fans just as SoCal wrestling fans had been hoping for. Names like Nakamura, Hiroshi Tanahashi and Katsuyori Shibata wanted to prove just how incredible they could be globally – and thus, considered themselves the “New Three Musketeers” in charge of shepherding in a new era.

The current iteration of New Japan’s LA Dojo can be credited to superstar head trainer Katsuyori Shibata. Himself a product of those efforts to turn the tides of NJPW domestically, Shibata-san would debut in 1999, collecting no titles in his first run, leaving in 2005 for the Japanese independent circuit. He would not stay away forever, returning in 2011 and forming the tag-team Laughter7 with Kazushi Sakuraba. Shibata would famously win the NEVER Openweight Championship – 3 times – with his first reign beginning at Wrestle Kingdom 10.

Shibata-san also has the 2017 New Japan Cup in his trophy case, a significant turning point in his career – and the NJPW U.S. experiment.

He used his victory in the tournament to challenge then-IWGP Heavyweight Champion Kazuchika Okada for the title. The bout took place at Sakura Genesis 2017, where Shibata would fall short in the match and collapse backstage, being rushed to the hospital where he was diagnosed with a subdural hematoma effectively sidelining his in-ring career.

“I hated to see myself as injured,” Shibata said in the California Dreamin’ YouTube miniseries. “My arms and legs are mobile. What can I do? Then I heard the news about the LA Dojo and I thought ‘This is it!'”

Shibata would join the new recruits in LA, playing the role of NJPW’s modern-day Masa Saito with genuine passion and purpose. A shooter with rarified gravitas, Shibata commands respect from both his trainees and the business executives back in Tokyo. His wrestling proteges walk the halls of Inoki’s dreams – joined by the standouts from Inoki’s old Santa Monica warehouse, who wrestle on New Japan STRONG. Together, they compete with other promotions as a puroresu alternative through live touring and marquee events that often feature bigger stars from Tokyo. “I thought this was exactly what our company needed, we have NJPW World and are attracting so many fans from abroad,” Tanahashi said in California Dreamin’. “I would love to get close to those of you outside of Japan. To do that we need a base of some sort.”

New Japan STRONG gives fans an 80s style weekly studio show with Kevin Kelly, Ian Riccaboni and Alex Koslov providing the soundtrack. It also creates a platform to showcase domestic fans the excursions of trainees from Tokyo, like Ren Narita, Shota Umino (aka “Shooter”) and Yuya Uemura.

“For the new generation of dojo recruits I see the same fearlessness we had,” TJ Perkins said in our interview. “I see it in multiple forms – they don’t fear failure in the process. And individually they have similar traits to some of us. I see a lot of my mentality in Karl Fredericks. He has a confidence in himself that is totally fortified. He believes everything he does will work out. That’s a rare quality, and something I have always had in my DNA.”

Rocky Romero echoed those statements, reflecting on his incredible career in New Japan.

“We were all huge fans of Japanese wrestling and wanted to wrestle for a major company in Japan. Every single guy had respect for the Japanese wrestling system and wanted to be mainstays [in the company].” he told MP. “I think the young guys share the same drive, determination, and love for what we’re doing. You have to. It’s the only way to get through those long days at the Dojo.

” Now a veteran presence in the locker rooms of AEW and NJPW, Romero has helped carry the vaunted Jr. Heavyweight division for more than a decade, while working to help create the next generations of superstars.

“The new LA Dojo has all that and then some, because they have support from the company,” Romero explained. “The O.G. LA dojo didn’t have that support. I think the sky’s the limit for all the current members, and I can truly say the future looks good for NJPW.”

Charged with creating a standalone wrestling product in four years, attendance figures at shows like Windy City Riot in Chicago and New Japan Resurgence in Los Angeles point to a massive success.

New Japan has melded the hard hitting style of puroresu with the spectacle of vintage pro-wrestling. AEW has followed the same blueprint; their product is at once nostalgic and fresh for fans trying to recapture the magic brought by kayfabe decades prior. That partnership is one of many wins that can be credited to Inoki’s initial vision of a U.S. territory. Whether it’s Jonathan Gresham wrestling a Billy Robinson inspired technical masterwork, or Jon Moxley toughing it out, trading violent strikes with Minoru Suzuki – Inoki’s original hopes for NJPW of America are finally turning into reality.

“I’m sure Mr. Inoki would be excited about NJPW being in business, still making an impact on pro wrestling,” Marquez said. “[If he were able to keep up], he’d have been all about the AEW relationship with the upcoming Forbidden Door pay-per-view!”

“I’d like to just see NJPW grow to new heights,” Romero told MP. “As things improve all over the world I’d really like to see the NJPW Strong roster grow and travel to Japan.”

Meanwhile, the promise of NJPW of America remains true to the initial idea set forth by Inoki-san in the early days of the original Inoki Dojo, with a growing event & production staff to help elevate the wrestlers’ platforms. “The reason there is an NJPW Strong is because of my relationship with Rocky Romero,” explained Marquez. “He along with Jeremy Marcus, another great friend, came to me to help them create the show, while I was shooting my Championship Wrestling from Hollywood program… and, of course I worked with them to get the show off the ground.”

We reached out to FiteTV for the NJPW pay-per-view buys, but couldn’t get a comment at the time of this writing. However, Wrestling Observer Newsletter has published consistent NJPW World subscriber numbers in the area of 130k – 150k since Chris Jericho and former IWGP U.S. Champion Kenny Omega squared off at the Tokyo Dome in 2018 – a healthy 30-50k being international fans.

While their partnerships with AEW, FiteTV and others in the West continue growing New Japan’s popularity in the West, it’s their dojo-trained talent and visiting Japanese wrestlers who really give audiences a chance to experience Inoki’s special theater of puroresu.

“The modern NJPW of America is so much better because I think they learned that people want to see a NJPW show,” explained SoCal Uncesored’s Steve Bryant. “Not, you know, local indie wrestlers in short matches with virtually no New Japan stars.”

NJPW Strong and the concurrent tours are all part of a wrestling renaissance that, in the past, helped build up legends like Christopher Daniels. For both regional SoCal fans and hardcore Japanese audiences, seeing who might break out of the pack – Clark Connors, Karl Fredericks, Alex Coughlin, The DKC, Kevin Knight – is all part of the fun.

The Lion once was sleeping… but now the Lion roars once more.

Date:

September 21, 2022

Category:

Features