Holy Land of Professional Wrestling: The Nippon Budokan

Holy Land of Professional Wrestling: The Nippon Budokan

By: Dr. Jonathan Foye

The Tokyo Dome. Ryogoku. Korakuen Hall. In Japanese pro wrestling, there are a number of iconic buildings with rich histories. Perhaps none of them, however, have the rich history and lineage of the 14,471-seat Nippon Budokan.

I interviewed several professional wrestlers about the Budokan, and I encountered a wide variety of perspectives on how important the place is to puroresu.

Naomichi Marufuji described it as, “a special place… It also sharpens my mind.” Another NOAH veteran, Takashi Sugiura, invoked a religious metaphor, telling Monthly Puroresu, “I think that Nippon Budokan is the holy land of professional wrestling, and I am proud to be able to compete there as a Japanese person.” Former All Japan and NOAH talent Richard Slinger described performing in the arena as “an experience I can never forget. Seeing and hearing the crowd with their excitement was a joy that made it hard to keep a straight face at times,” he said. “Sometimes you wanted to participate along with the fans with the enjoyment.”

Three of Tokyo’s great wrestling arenas, the Tokyo Dome, The Sumo Arena, and the Nippon Budokan, lie within a five kilometer radius of one another. The Budokan is found in Kitonomaru Park, near the Imperial Palace. It is an imposing but impressive figure on a picturesque landscape. Built during the 1960s in preparation for the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics, the building occupies a unique place in Japanese history. Modelled after the octagonal Yumedono temple in Nara, the Budokan is a symbol of Japan’s post-war rebuilding, of which the Olympics were a significant showcase.

The outside of the Nippon Budokan. c/o Creative Commons

In an interview, Japanese wrestling journalist and Monthly Puroresu’s editorial adviser Fumi Saito outlined the significance of the event and the building itself. “The Tokyo Olympics in 1964 was a symbol, it symbolized how the Japanese economy was building,” Saito said. “The Tokyo Olympics symbolized how ‘Japan is good again.’” Built specifically to host events like the Olympics’ Judo tournament, the building was Tokyo’s largest indoor sporting arena at the time.

While professional wrestling was not featured at the arena until 1966, the building’s roots in wrestling events run deeper. According to Saito, Rikidozan, the father of puroresu, was

keen to see the Olympics come to Japan. “As a professional wrestling superstar, he flew himself to the 1960 Olympics,” he said. “He also donated to the Olympic committee. … He played a Japanese part.” In a cruel twist of fate, Rikidozan did not live to see his dream of the Japanese Olympics come to fruition, or to set foot in the Budokan, dying after a run-in with a member of the Yakuza during the Summer of 1963.

Although the Budokan is now known in part for its use as a music venue, when The Beatles played the arena’s first rock concert in June 1966, the event was the subject of some controversy. “They were looking for a place to hold it, the biggest arena possible,” Fumi Saito recalled. “There was significant talk about western culture, rock, the Beatles.” Not everyone was happy with these influences making their way into the iconic Japanese sporting venue. “A Conservative political group said “Let’s not let the Beatles use the Budokan,” Saito said. “They held a rally and everything.”

Despite the furor, which extended to militants threatening the band members’ lives, the planned series of concerts went ahead. The Beatles performed five concerts over three days, one on 30 June, and two on each of the 1 July and 2 July 1966. Two of the concerts, 30 June and the first from 1 July were videotaped for posterity by NTV, later the TV partners of multiple professional wrestling promotions.

The Beatles performing at the Budokan, Creative Commons

Professional wrestling itself made its way to the Budokan later that same year. On 3 December 1966, the JWA promoted a card headlined by a defense of the NWA International Heavyweight Title (now part of All Japan Pro Wrestling’s Triple Crown). Champion Giant Baba defended his title against Fritz von Erich. “In 1966, Giant Baba was the biggest superstar in Japan,” Saito recalled. Standing across the ring from Baba, Fritz Erich was a hated gaikujin. The real-life Fred Adkitson from Texas played a goose-stepping heel role. While it sounds alarming today, the 1950s featured a number of Nazi characters in pro wrestling. “Fritz von Erich was one of them and he was a huge superstar,” Saito said. Rikidozan defeated Erich in the match, a best-of-three falls encounter. A clipped version of the match is available on YouTube.

The Middle Years

In the years to follow, wrestling promotions used the Budokan sparingly, although a number of classic bouts took place. Bob Backlund vs Antonio Inoki is one of the memorable examples. Taking place on 6 December 1976, the match ended with Inoki winning the WWF Championship in somewhat controversial fashion, after outside interference from Tiger Jeet Singh. Eventually, Inoki gave up the ill-gotten belt, and WWE does not recognise his reign today. For All Japan Pro Wrestling, the Budokan held special significance as something of a home base during the 1990s. Meanwhile, New Japan presented its big shows at Ryogoku and an annual Tokyo Dome show on 4 January, giving the arenas a de facto branding.

From 1990 to 1996, every show All Japan presented at the Nippon Budokan sold out, as the promotion’s unique, hard-hitting brand of professional wrestling resonated with fans. “During Misawa’s era, AJPW were running five to six [shows at the Budokan] a year, all packed,” Saito recalled. “That shows you how big a deal that big four era was.” After the ‘split’ that saw Pro Wrestling NOAH form, All Japan continued to promote shows in the building, albeit to diminishing returns. On February 22, 2004, the promotion ran a Budokan show headlined by the only singles meeting between Toshiaki Kawada and Shinya Hashimoto. While the match was a hard-hitting and historic bout, the card is significant for another reason.

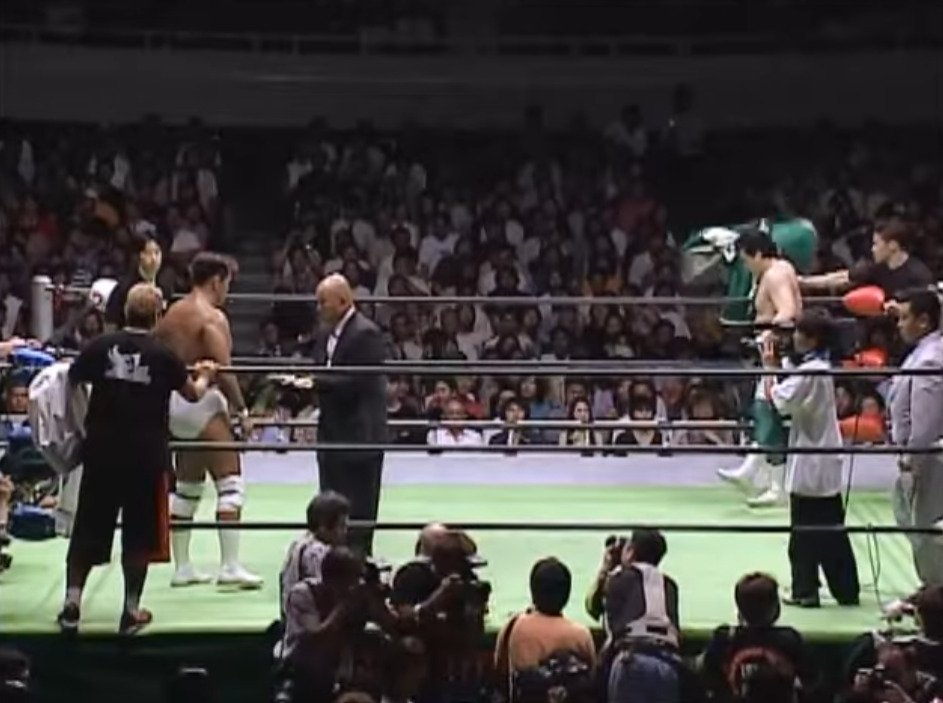

After the show, All Japan withdrew from the Budokan as then-President Keiji Muto downsized, moving the promotion’s big shows to Ryogoku. On July 27, 2001, NOAH ran its first Budokan card. The main event saw Jun Akiyama dethrone Mitsuharu Misawa to become the GHC Heavyweight Champion for the first time. For NOAH as a new promotion, running a show in a prestigious venue was a big step. It also held symbolism for the wrestlers who had previously left All Japan.

Jun Akiyama faces off against Mitsuharu Misawa for the GHC Heavyweight title.

According to Fumi Saito, the moment represented “Taking over the element and essence of what people loved during the ‘90s, very popular period of All Japan. Wrestling fans were asking themselves these same questions in their mind: Was it these guys we loved so much, or was it the All Japan logo we believed in?” he said. While the first card was a one-off for 2001, NOAH ran the Budokan twice in 2002. They then ramped up their appearances in the historic venue, with five in 2003. NOAH’s booking of the Budokan rose and fell with its business, with their last mainline show for over a decade being a memorial show for the late Joe Higuchi in 2010.

In 2011, after the Toho earthquake, New Japan, All Japan, and NOAH promoted a joint show in the Budokan to raise money for recovery efforts. The first night of All Together took place on August 27, 2011. Another show featuring a mix of talent from multiple promotions took place nearly two years later. On May 11, 2013, Kenta Kobashi wrestled his last match in the main event of Final Burning.

The Wrestling Observer’s Dave Meltzer called the event the “end of an era in Japanese pro wrestling.” While these historic shows served as memorable entrants into the arena’s history, they were outliers, as professional wrestling cards at the Budokan became a rarity before disappearing altogether for five years.

The Resurgence

After several years away from the venue, New Japan Pro-Wrestling announced in January 2018 that the Budokan would host the G1 Climax finals. This was the start of a new tradition, and the venue has hosted the finals every year since (except 2020).

New Japan Pro Wrestling were not the only ones to return to the historic arena. In late 2020, Pro Wrestling NOAH was now under the leadership of CyberFight and looking to lead a resurgence. Marking this with a show at the promotion’s spiritual home was something of a necessity, and the company booked the event for February 12, 2021. With the COVID-19 pandemic necessitating social distancing, the promotion was limited in the tickets they could sell. Still, Destination 2021: Back to Budokan drew a relatively impressive 4,196 people.

Shortly afterwards, STARDOM brought the Budokan its first joshi show since 1995, as All Star Dream Cinderella rocked the arena in front of 3,318 people.

Tam Nakano defeats Giulia at the Budokan to become Wonder of Stardom champion. c/o STARDOM

On September 18, 2022, All Japan returned to their former home for its first standalone show in 18 years. Its 50th Anniversary show featured appearances from past legends and a video of highlights, played only for the live fans in attendance. All Japan’s 50th Anniversary show attracted a strong crowd, with 4,780 people in attendance. At the time of the show, this was the biggest pandemic-era audience in the arena for any promotion other than New Japan.

Not to be outdone, NOAH once more booked the arena with a big draw card, namely WWE superstar Shinsuke Nakamura facing The Great Muta in the latter’s last singles match. NOAH The

New Year 2023 drew 9,500 people. On the card was Scottish wrestler Jack Morris, who wrestled Tim Thatcher. “The Nippon Budokan is world famous, and not just through wrestling,” Morris said. “I’m a huge music fan too so knowing that artists such as The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Queen, Aerosmith amongst so many other legends of music have played at the venue is very cool! And of course the history of it in wrestling and martial arts is huge too. From the most recent Muta vs. Nakamura match at NOAH’s New Year show 2023, to when Muhammad Ali fought Antonio Inoki. I have a huge sense of pride to say that I’ve wrestled there.”

The Future

Over the years, the number of wrestling shows at the Nippon Budokan has ebbed and flowed along with the rest of Japan’s industry. What started as a relative novelty in the arena’s early period became commonplace during the boom of the 1990s, only to contract again during pro wrestling’s ‘dark ages.’ Once more, the Budokan found a prominent place in fans’ imaginations and drew people back to see live wrestling in a unique setting.

While no future wrestling shows have been announced for the Budokan at the time of writing, this is likely to change soon. Presumably New Japan will run the G1 Climax finals in the arena, and NOAH will return for their New Year’s Day show.

As the COVID-19 pandemic eases, and Japan’s wrestling industry recovers, more memorable cards from puroresu’s “holy land” will no doubt follow.