By: Colin McNeil

Owen Hart is a name that comes with baggage.

Talk to a wrestling fan today and the first thing they’ll mention is his tragic and untimely death. After that, they’ll reminisce about his breakout run in WWE, when he was memorably pitted against his superstar brother Bret. They might even bring up his time spent under the mask of The Blue Blazer.

But few will tell you about his years in New Japan Pro Wrestling.

This is not a story about new foundations, feuding brothers, black-hearted heel turns or a baby-blue superhero gimmick. And it’s not a story about tragedy. This is the story of how one of the most talented wrestlers of a generation made history 8,000 kilometers from home.

It’s the story of Owen Hart in Japan.

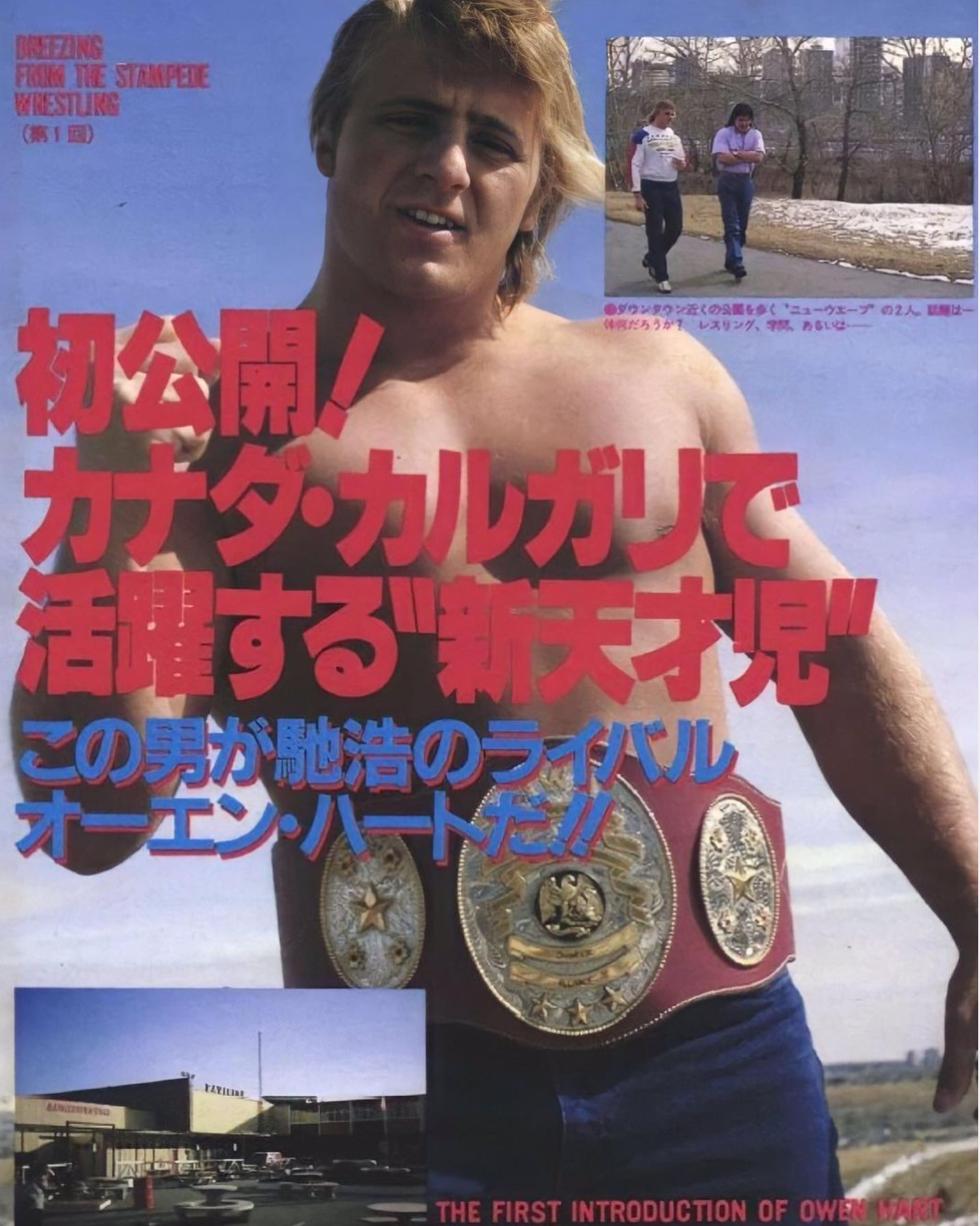

On paper, Owen Hart’s journey in Japan began on August 24th, 1987 – the night of his debut match for NJPW. But while that date marks his first in-ring appearance, Hart’s arrival in Tokyo was anticipated long before he actually set foot on the iconic cerulean blue canvas. By that time a full-blown mythos had already materialized around the youngest member of the Hart Family.

It’s a mythos that stretched from Calgary, Canada half a world away to Japan.

His early in-ring work in the UK and for his father’s Stampede Wrestling promotion had begun to swing the spotlight toward him. But, according to wrestling journalist and historian Fumi Saito, the overseas legend of the Calgary Genius is inextricably intertwined with one man: Hiroshi Hase.

Hase, who later became a national politician and cabinet minister under Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government, was himself a rookie wrestler cutting his teeth abroad in 1987.

His own foreign training excursion would take him north to Hart family patriarch Stu Hart’s Calgary-based Stampede Wrestling, and he brought all the attention of the Japanese wrestling press with him.

Hase was a popular subject for Japan’s weekly wrestling magazines – no surprise, as he was a former Olympian and a trainee of the legendary Riki Choshu – and he made sure Owen Hart became part of his own story there.

The two often worked together in Calgary – with Hart teaming with Stampede mainstays like Ben Bassarab, or a young Brian Pillman, and Hase on the opposite side of the ring as one half of a team dubbed The Viet Cong Express. They built a rivalry in the ring, and a friendship outside it.

Before long, stories and photos began to make their way back from the Great White North. Stories about Hase’s greatest rival, a flying genius out of Canada. The baby Hart brother who could be the second coming of past Stampede exports like Dynamite Kid or Davey Boy Smith.

And just like that, thanks in large part to Hase, the legend of Owen Hart arrived in Japan long before the man did.

When Hart did finally step into a Japanese ring for the first time, it was late August at Korakuen Hall in front of a crowd of some 1,800 people. It was day one of a typically grueling 24-event, month-long national tour called Sengoku Battle Series ’87.

His debut match saw him paired with journeyman English wrestler Mark Rocco against two men who would go on to define the sport of pro wrestling: Keiji Mutoh and the future Jushin Thunder Liger, Keiichi Yamada. After 13 minutes, it was the foreign team left counting the lights while the Japanese wrestlers’ arms were raised.

And that formula was often repeated during Hart’s first tour in Japan: Hart teaming with fellow foreigners like Rocco, or Scott Hall, or Dick Murdoch against domestic talent. At first glance, it looked like a tried and tested crowd-pleasing recipe: invading villains matched up against local heroes.

But while so many of his non-Japanese tour contemporaries fit snugly into that “foreign heel” role, Hart never wore the proverbial black hat. Even in matches where a tag partner was working heel against a pair of hometown heroes, the boy from Calgary kept it clean. No cheating, no antagonizing the crowd, and a lot of fighting spirit.

“Owen Hart never worked heel here,” confirmed Saito. “He was a clean guy, an athlete, a likable guy, always smiling.”

As to why Hart never played a rudo role in Japan, we have to consider that it was more than just Hase’s hype that followed him there. In a more implicit way, so too did the lineage and legacy of the Stampede wrestlers who came before him. Calgary’s Stampede Wrestling and NJPW had been exchanging talent for years, and fans in Japan were no strangers to the talent that emerged from Stu Hart’s infamous dungeon.

Owen Hart had the Calgary look all over him, and fans in Japan understood what that meant.

“If wrestling fans see his work and his costume – definitely that guy’s from Calgary,” said Saito. “Calgary wrestlers are no-nonsense. They come in and wrestle, like Dynamite Kid did, Davey Boy did.”

And like Dynamite Kid before him, Owen Hart was more than just no-nonsense. He was innovative, electrifying and gifted physically – destined for more than cheap heat at the expense of the Korakuen faithful.

And Hart would hold championship gold in NJPW, but not on his first tour. A September 17th loss to Kuniaki Kobayashi for the IWGP Junior Heavyweight Title would be the closest he’d get to a NJPW belt in 1987, and soon afterward he’d be on his way back to Canada.

It wouldn’t be long before the Calgary Genius reappeared in Japan: just a few days into 1988, he returned to a NJPW ring for his second tour with the promotion. Waiting for him was Hiroshi Hase, the man who had evangelized his legend to the Japanese press the year prior. And it was Hase who would hand Hart his first loss of the year. Screams of “Owen Hart!” could be heard from the crowd as the two clashed half a world away from where they first met. While the vocal support for Hart wasn’t quite as loud as the screams for Hase were, it’s clear that this young Canadian wrestler was connecting with the Japanese crowd.

There would be no title shot this tour, but Hart would still manage to make history, participating in the very first Best of the Super Juniors tournament. He placed fourth overall, two spots below Hase and two above the future Jushin Thunder Liger Yamada.

Hart would fly home again in February, but fans in Japan would only briefly be deprived of his signature handstand backflips and acrobatic rope work. He’d return in May, destined to make history once again.

Just five days into Hart’s third tour in Japan, he would challenge his friend Hiroshi Hase for the junior heavyweight title. And this time, after a 13-minute barrage of moonsaults, rolling cradles and suplexes, he’d win.

On May 27th, 1988, Owen Hart became the first non-Japanese wrestler to hold the IWGP Junior Heavyweight Championship, his hand raised to chants of “Hart-o! Hart-o!” from the elated Sendai crowd.

“It had to be Hiroshi Hase to put him over,” recalled Saito. “Perfect opponent, perfect match to establish Owen Hart to be your next Dynamite Kid.” He was not a one-hit wonder, either. On June 10th, Hart successfully defended the title against Yamada in a match that, more than 30 years later, would impress if it were put on today.

In a war of athleticism, skill, and counter moves, the two cruiserweights packed as many gasp-worthy moves and as much subtle storytelling as possible into 13 and a half minutes.

It’s with Yamada that Hart would have some of his best matches in Japan, and perhaps of his career. There were few wrestlers, even in the ranks of NJPW’s vaunted junior heavyweight division, that could keep his pace and match his athleticism the way Yamada could. The two just seemed to click. Whatever the year and whatever the outcome, their matches always felt exceptional.

On June 24th, Hart would lose the junior heavyweight gold to the first man to ever hold it, Shiro Koshinaka. The match was a clash of styles that proved (if proof was ever needed) that Hart could work at a different pace if necessary. But his work with Koshinaka never quite clicked the way the clashes with Yamada or Hase did.

“Owen Hart didn’t feel Koshinaka was the right opponent either,” said Saito. “Hiroshi Hase – great opponent to work with. Keiichi Yamada – [they] know everything about each other, that’s great. But he didn’t feel as comfortable working with Koshinaka. He’s more of a Japanese style guy.”

It’s a reminder that during his time in Japan, Owen Hart was at his best when he was paired with wrestlers whose style matched his own.

And that was the case for his final NJPW match of that year, when he beat Keiichi Yamada in front of a 10,000 strong crowd in Nagoya. There could hardly have been a better 1988 send-off for the Calgary Genius.

While Owen Hart was winning the hearts of Japanese crowds with every flying headbutt in the ring, he was living the life of a friendly, if modest, man outside of it.

As Saito recalls, he was down-to-earth when in street clothes, quickly making a positive impression on every young fan who waited for him in a hotel lobby or ran into him at the local grocery store.

And he was thrifty. Hart walked everywhere instead spending money on transportation. He would seek out the cheap places to eat, charm gym owners into working out for free, and do his own laundry with the help of fans he met along the way.

But what about those infamous Owen Hart ribs?

By now anyone with a passing interest in Hart’s career is familiar with his love for outlandish but good-natured practical jokes. From Vince McMahon himself to his own brother Bret, there are apparently few people in WWE during the 1990s who can’t count themselves victims of an Owen Hart prank.

But according to Saito, who knew Hart personally during his time in Japan, the Calgary Genius was not the same hell-raising prankster around his peers overseas, particularly on his first tour.

“Actually he was first very, very careful,” explained Saito. “Because on the same tour there was Dick Murdoch, young Scott Hall … “Cowboy” Bob Orton. Owen was the baby of the tour – the youngest guy.”

Less than two months after his third tour wrapped in Japan, Hart moved on to what he no doubt thought would be greener pastures – the then-WWF – donning a blue and white feathered costume in his first run as The Blue Blazer. Despite having all the in-ring talent in the world, the masked superhero identity fell flat for Hart, and he left the WWE midway through 1989.

New York’s loss would be Tokyo’s gain. After a handful of dates in Canada, Owen Hart was once again bound for Japan. That first post-Blue Blazer tour culminated in a September 21 Junior Heavyweight title match against Naoki Sano. Hart lost the match, and it would be his last chance to reclaim junior heavyweight gold in Antonio Inoki’s company.

During the next few years, Hart wrestled across the globe, working in Mexico, Germany and of course Japan. But while the opportunities for hardware in NJPW dried up, the great junior heavyweight matches didn’t. Classics against the likes of Chris Benoit as Pegasus Kid, Mutoh and Yamada (now Jushin Thunder Liger) continued to thrill Japanese audiences and western tape traders alike. And in the spring of 1991 he participated in the second Best of the Super Juniors tournament, held three years after the first.

But eventually, promotions close to home came calling again. And after a brief trial stint in WCW, Hart returned to the WWE– this time for good.

Hart’s final match in a New Japan Pro Wrestling ring took place on April 28th, 1991. In the opposite corner stood Jushin Thunder Liger. Both wore the same red and white colors – Liger in his usual costume and Hart sporting the colors of his native Canada – as if to nod to the fact that Liger and Hart were kindred spirits between the ropes.

It isn’t long after the opening bell of this match that Hart’s ring rope acrobatics elicit gasps from the crowd. They “ooh” and “ah” as he’s suplexed out of the ring by Liger. They hold their collective breath as a flying headbutt from the top rope connects with a laid-out Yamada. There are even cries of “Owen Hart!” that make it through the chorus of Liger chants. It’s a match with all the pace, athleticism and technical prowess you could want out of a junior heavyweight classic of the era.

While his time in New Japan Pro Wrestling had come to an end, Hart would return to wrestle in the country twice more – once for a handful of matches in Genichiro Tenryu’s WAR promotion in 1992, and again in 1994 as part of a WWE tour of the island.

Five years after his last in-ring appearance in Japan, and eight years after his final match in NJPW, Owen Hart died. It happened on a Sunday night, Monday morning in Japan.

Saito was working as a staff writer at Weekly Pro Wrestling the day it happened. It was deadline day for the magazine. Stories, images, layouts and covers for the upcoming issue are locked and finalized on Mondays. All of that went out the window when the news reached Japan.

Saito recalled the editorial team scrambling to cover the tragedy that day and, at the last possible minute, changing the front of the magazine. Instead of what was originally planned for the edition, an image of the Calgary Genius from his history-making junior heavyweight title match in 1988 graced the glossy cover.

Inside the magazine, accompanying the photo of Owen Hart smiling with the IWGP Junior Heavyweight Title held triumphantly over his head, were words penned by an old friend – Hiroshi Hase.

“Somebody made the phone call to [Hase] … and he wrote an essay. He wrote a poem right away, saying goodbye to his friend,” recalled Saito.

For the first time, and the last time, Owen Hart was on the cover of Weekly Pro Wrestling in Japan.

Owen Hart’s entrance theme in NJPW was called Hallucination, and that is sometimes what his time in Japan feels like. A body of work largely unknown or forgotten by North American fans today – overshadowed by both his career in WWE and the tragic events of later years.

But it wasn’t a hallucination. It was a generational talent at his best and in his element. Unencumbered by half- baked superhero gimmicks, or the need to shock audiences in an era of attitude, Owen Hart the wrestling artist painted early masterpieces on the canvas of the squared circle.

“In a Japanese ring there is no promo. There is no backstage skit. There is no silly storylines,” said Saito. And that’s where he felt most comfortable.”

Date:

August 5, 2022

Category:

Features